Celebrate the Holiday Season in Japanese

Welcome back to our “Video & Article” series with tutor Miki. In this article and video, Wasabi Tutor Miki teaches you phrases and vocabulary related to the Holiday Season in Japanese. And more importantly, you can learn about some important traditions and customs that come with New Year’s celebrations in Japan!

| Table of Contents [Introduction] [Christmas] [お正月 – Japanese New Year’s] [New Year’s Traditions] [Vocabulary List] |

[Introduction]

In this lesson, Miki introduces phrases and vocabulary related to the Holiday Season in Japan. While Christmas is only a minor event, celebrating the New Year is an important custom usually celebrated with one’s family. Learn what happens on Christmas and for New Year’s in Japan and learn all the phrases you need to get through these final weeks of the year!

[adsense]

[Christmas]

First, let’s talk about Christmas. Christmas is called “クリスマス” in Japanese. In Japan, Christmas is actually more of a couple’s holiday than a holiday spent with your family. In other words, many people in Japan spend Christmas with their partners or just with friends and not with their family.

Miki also notes that many people do not celebrate Christmas for religious reasons (although some may!) but that it’s rather a day to enjoy the wintery atmosphere made warmer by illuminations (especially in Tokyo!), exchange small presents or have a romantic date with your partner.

On Christmas eve, which is when Christmas is usually celebrated in Japan, many people eat fried chicken or have a Christmas Cake with a Santa Clause figurine on top. The cake is often a “ストロベリーショートケーキ”, since strawberries are in season in winter in Japan, and Santa Claus is called “サンタさん” in Japanese.

Many kids in Japan are taught just like in many other countries that Santa Claus comes to visit only those kids that have behaved well throughout the year.

クリスマスイブはサンタさんが来る日。

Christmas Eve is the day Santa Claus comes.

On Christmas, many people say “メリークリスマス”, which is often shortened to “メリクリ”.

[お正月 – Japanese New Year’s]

After Christmas, many people who live in the city to back to spend New Year’s Eve with their families who often still live in rural areas. The new year is called “新年” or “正月” in Japan. Unlike Christmas, where most shops and restaurants are open, a lot of places are closed on New Year’s Eve and many small shops are closed for at least a day if not more during the first week of January.

“Happy New Year” is “新年あけまして、おめでとうございます”, or with friends, you can just shorten it to “あけおめ”. But don’t forget that both “メリクリ” and “あけおめ” are very casual expressions and it’s not appropriate to say these phrases to your superiors at work or to your elders.

If you want to level up your New Year’s greeting from just “新年あけまして、おめでとうございます”, you can add “今年もよろしくお願いします”, which means “I humbly look forward to a continued good relationship during the new year as well”.

If you want to be more casual, you can say “あけおめ、ことよろ!”, which just shortens the long “明けましておめでとうございます。今年もよろしくお願いします” to a couple of syllables.

Another phrase that is commonly used is “良いお年を!”, which means “I hope you have a great year!”.

[New Year’s Traditions]

On New Year’s Eve, it is a common tradition in Japan to eat Soba noodles. Soba noodles are a speciality in Japan which are made from buckwheat. The Soba eaten on New Year’s Eve is called “年越しそば”. “年越し” means “The passing year”. “年越しそば” symbolises a long life because the Soba noodles are long, like Ramen noodles. They represent a prayer for long life.

Tutor Miki recalls that she used to eat handmade Soba near her house as a kid with her family around one hour before the new year. She always loved the Toshikoshi-Soba served in a hot Dashi broth with Tempura, a poached egg, and sprinkled with some green onions while watching the New Year’s specials on TV and being allowed to stay up late with her siblings.

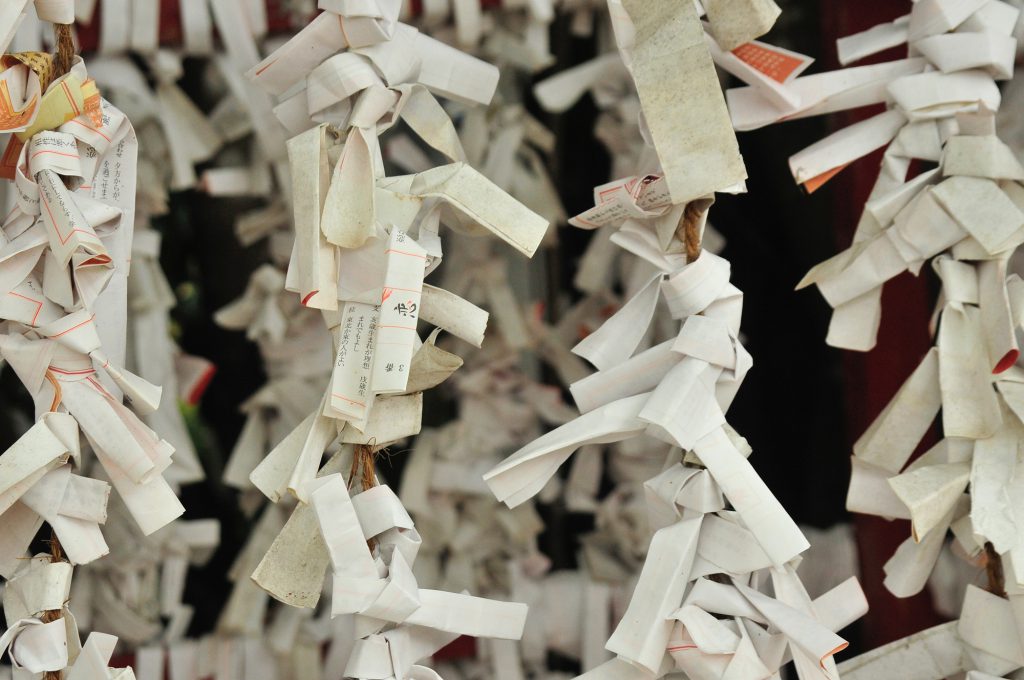

And when the countdown is finished, that’s not where it ends at all! People energetically go and visit shrines to pray to the Gods and Buddha for good fortune for the new year. This first visit to the Gods is called “初詣”. Many children also love to go because they get to draw fortune-telling paper strips called “おみくじ”.

It depends on the shrine, but usually, you can buy a paper strip that will tell you your fortune for the new year. You draw the paper yourself out of a box. On the paper, you will find different levels of fortune. The options are as follows:

大吉(Daikichi)Excellent luck

中吉(Chuukichi)Fair luck

小吉(Shoukichi)good luck

吉(Kichi)average luck

凶(Kyou)bad luck

小凶(Shoukyou)a little bad luck

中凶(Chuukyou)fair bad luck

大凶(Daikyou)very bad luck

初詣でおみくじを引いたら大吉だった!今年はいいことありそう!

I drew a fortune paper on my first visit to the shrine! I bet good things will happen this year!

If you aren’t sure where to pick a fortune paper in a temple or shrine, you can ask, saying:

おみくじはどこですか?

Where can I find the fortune-telling paper strips?

After finishing “Hatsumoude”, you should be plenty exhausted and ready to go to bed for the day.

Other then the Toshikoshi-Soba and Omikuji, on New Year’s, you will find many other dishes related to fortune. One of the main dishes is called “おせち料理”. This is traditional Japanese New Year’s food presented in bento boxes which are piled on top of each other. The dished contained inside often symbolise long life and other blessings.

For example, beans are called “豆” in Japanese. “Mame” (usually just in Hiragana) can also mean “diligent” and is used in the phrase “まめに働く”, which means “To work diligently”. Using beans in “Osechi Ryouri” expresses a wish for a healthy body to work hard in the new year.

おせち料理のまめは「元気に働けますように」という意味があります。

Beans in Osechi Ryori express a wish for a healthy body to work diligently in the new year.

That’s we have on the holiday season today. Thank you for reading this article, and please feel free to consult our native Japanese language teachers if you have any further questions! You can also discuss this article on our official “Japanese Learning Group” on Facebook!

| 年末年始 | Nenmatsunenshi | New Year’s holiday, period between the end of the old and beginning of the new year |

| 添える | Soeru | To garnish, to accompany |

| クリスマス | Kurisumasu | Christmas |

| サンタさん | Santa-san | Santa Claus |

| メリークリスマス | Merii kurisumasu | Merry christmas |

| メリクリ | Merikuri | Shortened form of “メリークリスマス” |

| 新年 | Shinnnen | New Year |

| 正月 (often: お正月) | Shougatsu (Oshougatsu) | New Year, New Year’s Day |

| (新年)あけましておめでとうございます | (Shinnen) akemashite omedetou gozaimasu | Happy New Year |

| あけおめ | Akeome | Shortened form of “あけましておめでとうございます” |

| 今年もよろしくお願いします | Kotoshi mo yoroshiku onegaishimasu | I look forward to a continued good relationship in the new year. |

| ことよろ | Kotoyoro | Shortened form of “今年もよろしくお願いします” |

| 良いお年を | Yoi otoshi wo | Have a good New Year |

| 年越しそば | Soba | Soba eaten on New Year’s Eve |

| 初詣 | Hatsumoude | First visit to a shrine in the new year (usually after midnight) |

| 吉 | Kichi | Good fortune (can be combined with 大 (big), 中 (normal), or 小 (small) to express the extent of the good fortune) |

| 凶 | Kyou | Bad fortune (can be combined with 大 (big), 中 (normal), or 小 (small) to express the extent of the bad fortune) |

| おみくじ | Omikuji | Fortune-telling paper strips |

| おせち料理 | Osechi ryouri | Food served during New Year’s holiday (often symbolising blessings for the New Year) |

| 豆 | Mame | Bean, legumes |

| まめ | Mame | Diligent, hardworking, faithful |

| まめに働く | Mame ni hataraku | To work diligently |